Back in 1999, at the peak of the dot.com bubble, I wrote an article

for Tocqueville Asset Management, the firm I had founded in 1985. It was

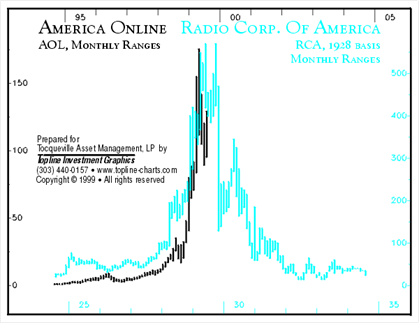

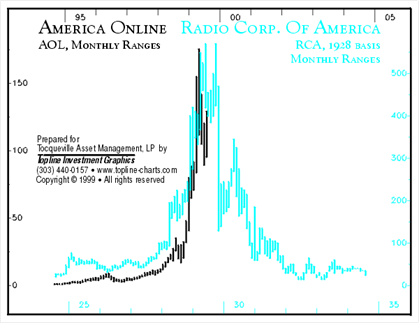

entitled “AOL, RCA and The Shape of History” (Tocqueville Asset Management, December 1999) and was inspired by the chart below, borrowed from that Thanksgiving’s issue of The New Yorker. It compared the 1920s bubble in the shares of RCA to the stock performance of AOL in the late 1990s:

As a preface, I quoted from a report prepared for RCA in 1929 by Owen

Young, then Chairman of General Electric, about radio in the 1920s: “[It]

has helped to create a vast new audience of a magnitude which was never

dreamed of… This audience, invisible but attentive, differs not only in

size but in kind from any audience the world has ever known. It is in

reality a linking-up of millions of homes.”

It was clear to me that radio — especially when combined with the

growth of automobile and air transport — revolutionized the perception

of space and time in the 1920s, just as the Internet and globalization

are doing today. It also reminded me of a piece of sage investment

wisdom: never invest in a company that promises to change the world. The

point is not that the most promising companies do not deserve their

reputation. Rather it is that, once a business’s prospects are widely

recognized, those prospects affect its stock price, often dramatically.

This makes the risk/reward ratios unacceptable.

The story of radio is instructive: it did change the world and

“disrupted” traditional news and advertising media. In the six years

between 1922 and 1928, sales of radio sets rose from $60 million to $843

million! RCA, as the largest manufacturer of radio sets and also the

leading broadcaster, saw its earnings grow from$2.5 million in 1925 to

$20 million in 1928; its stock price rose from $1.50 in 1921 to a high

of $549 in 1929. Yet few of radio’s early developers and participants

made lasting gains from this, as competition and industry changes eroded

the hoped-for profits.

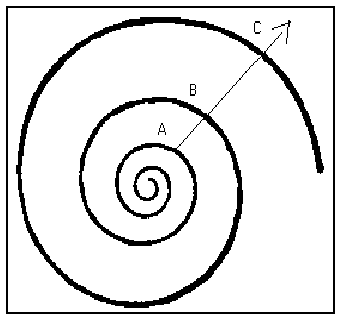

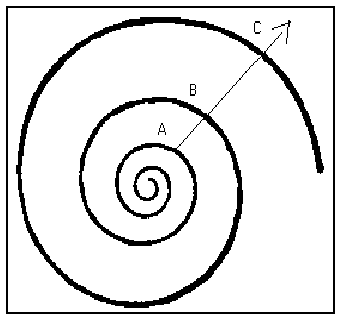

As Mark Twain is reputed to have said: “History does not repeat

itself but it rhymes.” My own explanation of the shape of History is

illustrated in the following graph.

In this illustration, point B will display enough similarities with

point A so that economists with a good memory will experience a strong

sense of déjà vu. Yet, between these two periods, many structural

changes will have taken place – in societies, in world trade and in

technology, for example. As a result, point B will resemble point A, but it will also be different enough that precisely

forecasting what C will look like or when it will occur is all but

impossible. The only certainty (for me) is that there will be a point B.

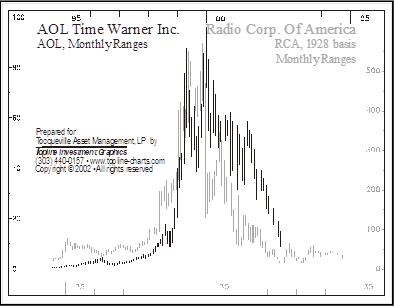

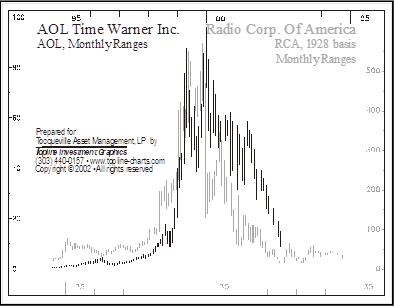

Investors in RCA at the top of the 1929 speculative boom were right

about radio’s fundamentals: the number of households with radio sets

grew from 2.75 million in 1925 to 10.25 million in 1929 and, through the Great Depression,

to 27.5 million in 1939. But the investors were wrong about RCA’s stock

price. As we see in the chart below, included in a November 2002

follow-up paper, the fate of AOL’s stock following the 1990s dot.com

boom was not very different.

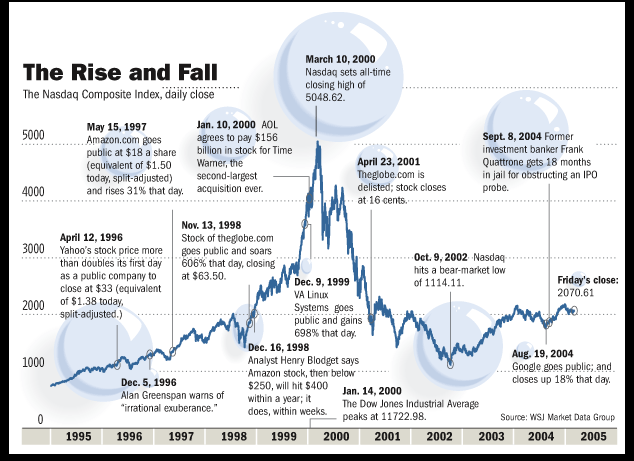

AOL was selected to illustrate what happened more generally to

internet stocks once the dot.com bubble burst. I hope the following

graph will awaken in our readers some memories of how history often

rhymes:

Source: Wall Street Journal Data Group

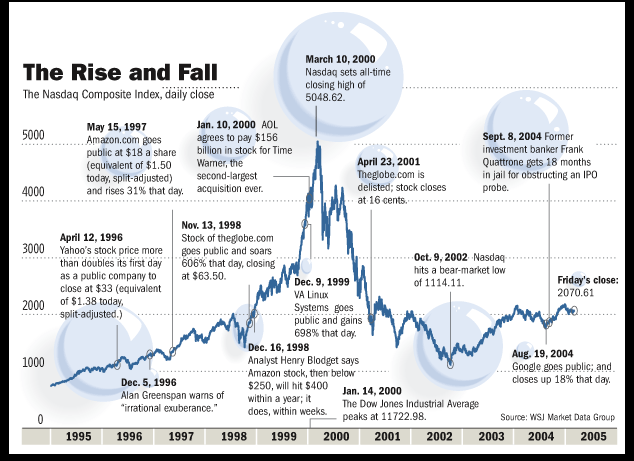

What triggered the current article was my watching the stock market

performance of many of the new industries, as illustrated by the

so-called FANG stocks (Facebook, Amazon, Netflix and Google) as well as

those of some other “disruptors.” The chart below of the performance of

the S&P 500 information technology index relative to the total

S&P 500 index gives some idea of the disparate performances of the

“disruptors” against the overall index. The ratio of the two is close to

the level it had reached at the top of the dot.com bubble, in 1999.

Source : FT Market Forces, JUNE 29 2020

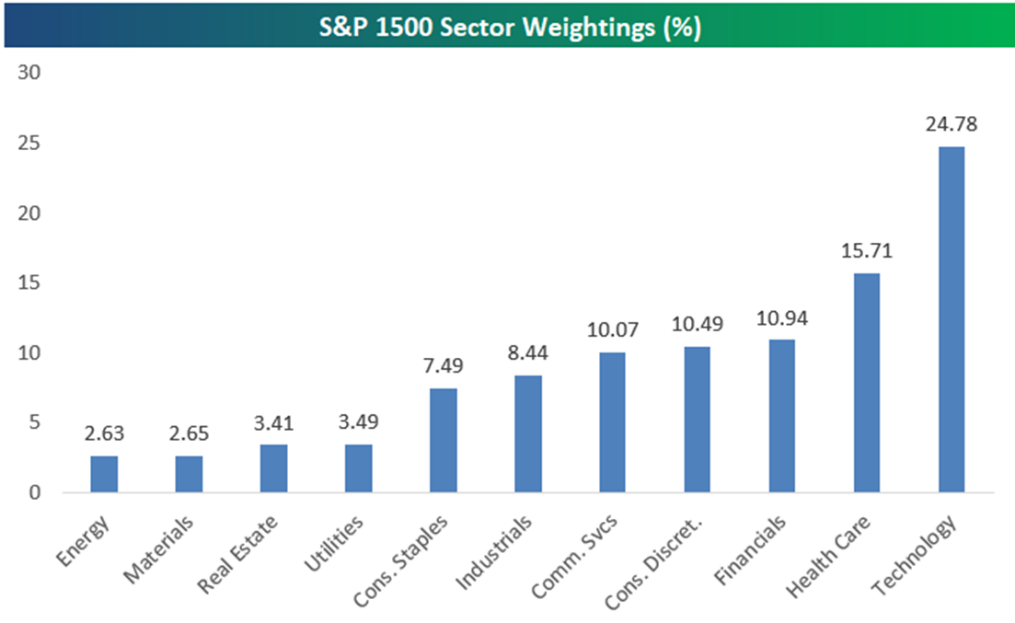

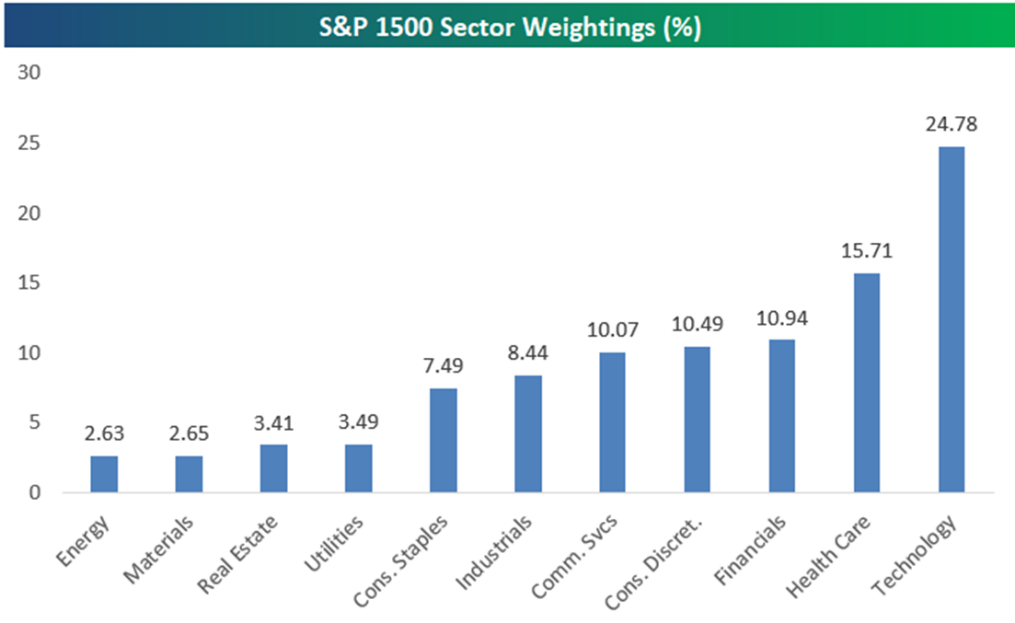

Particularly striking is the fact that the technology and health care

sectors now represent 40% of the total capitalization of the S&P

500 index. Furthermore, the four companies in the so-called FANG index

account for 22% of the total capitalization of the 500 companies in the

S&P index. (Note: this index only counts 4 companies since both

shares classes of Google, which are listed separately, are included). If

we also included Apple and Microsoft, the so-called FAANGM would add up

to 25% of the capitalization of the S&P 500.

Source : BESPOKE 4/20/20

Needless to say, the weight of these new-era leaders in the leading

indexes has been a major factor in the behavior of the market as we

usually follow it. For example, the “narrow” FANG index has risen almost

62% year-to-date while the total S&P 500 index has gained only

4.8%. Furthermore, since the FANGs are included in the broad index, we can infer that the rest of the market has not gained much in this “great” recovery.

One of the most reliable signals of market excess is its narrowing

breadth – when the performance of a relatively narrow sample of

companies takes off, while the broad market fails to follow. The “Nifty

Fifties” in the 1970s were such a sample, which few of today’s investors

can remember first-hand. Major institutional investors had been

traumatized by the unexpected 1969-1970 recession on the heels of a long

and prosperous expansion that had led a number of reputable economists

to declare the economic cycle vanquished and recessions a thing of the

past. As a result, these institutional investors had concentrated their

portfolios on fifty or so companies of the highest quality. They had

potential to grow fast and were considered “recession resistant.” This

relatively small sample did temporarily outperform the economy and

especially the stock market, hence their nickname of the “Nifty Fifty.”

(They were also known as the “Vestal Virgins” because analysts could

find no fault in them.)

Something similar happened in the late 1990s with the dot.com

companies around the development of the Internet, an episode which many

younger investors remember, even if they have forgotten AOL and other

Internet pioneers.

Both of these episodes were initiated by smart and sophisticated

people, expert at articulating the case for the companies or the

industries they were promoting. The problem arose when a large crowd of

investors joined them, pushing up prices to unreasonable levels. In each

of these examples, a small sample gained a price advance against the

market at large, which is why the breadth of the market advance deserves

attention.

In my view, a similar fad has developed with the FANGs or FAANGMs

today. The details and the techno-socio-economic environment may differ,

but we should not forget that History usually does rhyme… eventually.

François Sicart – July 3rd 2020

https://www.sicartassociates.com/rca-nifty-fifty-aol-and-fangs/